Like his sister before him, Gulumiza wasn’t a ‘planned’ baby. Sure we’d talked about the possibility of having a second and hoped it would happen at some point. But, given how long we’d had to wait for Netanya and the fullness of joy that God had brought our way with her, we were in that zen place where it was fine if it happened and fine if it didn’t.

Or so I thought.

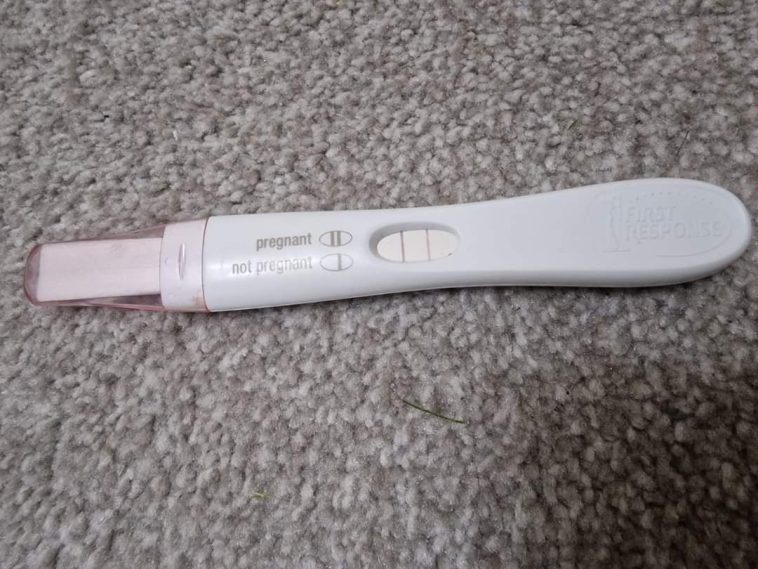

When Diana broke the news that we were expecting (a whole dramatic story of its own), I quickly found out a depth of joy I didn’t know I had. Had I suppressed the hope of another child, just in case it didn’t happen? Was this overflow of raw excitement simply a result of bottling it all in? Or was it simply the joy that came with finding out I was going to be a father again, period? I don’t know. A part of me wants to believe it was all about the good news and not take away anything from the moment. Another feels it might be a combination of both.

No matter.

I cried.

Again.

I had always hoped to have a daughter. Diana a son. When we had Ayinza, Diana didn’t want us to find out the sex. I on the other hand was furious the pee stick couldn’t tell us the sex! With Amariah, the roles were a little reversed. D was fine with knowing the sex, I felt we’d started a mini tradition with Tanya that we had to maintain. In the end, we agreed to find out at birth. Throughout the pregnancy, I kept changing my mind about whether I thought it was a boy or a girl.

With Netanya, Diana got a lot of heartburn. With Shoroora, not so much.

It must be a boy, I thought.

With both pregnancies, Diana hardly had any morning sickness.

It must be a girl again, I thought.

Towards the end though, I was sure it was a boy. Diana asked me why I was so certain. I told her I just knew. I also told her I was very anxious about the prospect of being a father to a boy. She asked why.

Those that know me also know that my relationship with my father was a difficult and complicated one. We fought and argued a lot. He always seemed to expect more from me than I could give and I always felt that he saw me through the lenses of his own dreams and aspirations rather than mine. When, in my first term in a new school, I scored 99 in English, 95 in social studies, 70 in science and 68 in maths, his response was “You know Ganzi, mathematics isn’t hard. You are my son. You can do better.” He then went on to tell me the story he almost always told. How he, a last born of peasant parents, who had lost his father while in primary school, and walked 10km to school every day-and another 10 back home- had always topped his class in maths.

So I worked hard and sure enough, at the end of the second term, came back home with a report card that said I had a 74 (distinction 2 at the time) in maths and distinction one (above 75) in all the other subjects. I had come second in my stream and third overall.

Unlike most times when I held on to my report card until I was asked for it, I ran home from school as fast as I could and placed it on his bed, then went to my room and waited for him to return from work, read the report and summon me. He was going to be proud of me, I thought. Finally, I was living up to the billing of a professor’s son. Sure, mum too would be proud. But mum was always proud of me. It was his love and affirmation I sought, not because mother’s wasn’t important, but because his was the one I was yet to earn.

Or so I thought.

Sure enough, he came home that evening and looked at the report card and summoned me.

I walked into his room with a swagger, a triumphant entry into Jericho. Surely the walls had been broken. Surely today I would be my father’s son. He kept his eyes on the report card for a while and then looked up to me.

“Next term I want a Distinction1 in maths,” he said.

I was nine years old at the time. And although I didn’t know it then, it was in that moment that any interest I had in the sciences and (intentionally) being like my father died. From then on, it would be rebellion.

So why was I anxious about being a father to a boy? Well, because in 2021, almost three decades after this incident, the prospect of breaking a boy’s heart the way my nine-year-old heart was broken lurked at the back of my mind. All my life I’d heard of ‘daddy’s girls’. I’d seen them all around me. I’d been both shown and socialised into thinking that when it comes to daughters, fathers’ wells run deep. When Netanya was born and thrust into my hands, I knew it to be true.

But with the boy child, I wasn’t so sure.

With a boy, the best I could hope for- or so I thought- was that he was a mummy’s boy.

Like me.

But society scorns mummy’s boys. They are in many ways the antithesis of what a man should be.

And so, my worst fears about myself and my best hopes for my wife’s relationship with a son both ended in tears. Whichever way you sliced it, having a boy was a terrifying prospect.

He was due on the 14th of June, 2022, exactly two weeks before his big sister’s birthday.

As the day grew closer, I kept telling Diana I strongly thought it was a boy. I said it with as much excitement in my voice as I could muster

Secretly, I was in panic mode.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!