In the glow of a smartphone screen, a quiet epidemic is claiming the hopes—and sometimes the lives—of Nigeria’s youth. ODIMEGWU ONWUMERE writes that what begins as a harmless bet on a football match has spiraled into a national crisis of addiction, debt, and despair, leaving behind a trail of stolen futures and whispered goodbyes on social media

The glow of a smartphone screen is the last light some of them ever see. For Onoh Chukwuma Richard, that light was a window into a world of impossible odds and crushing debt. In 2023, in Abia State, the 20+ year-old started a live video on Facebook. His face, young and full of a pain too heavy to carry, filled the frame. “Today is my last day on earth!” he announced to the handful of viewers watching, unaware they were witnessing a farewell. “I am going to meet my maker.”

He had lost N2.5 million to the quick, seductive promise of sports betting. A portion of that money, N1.2 million, was not his. The shame, he explained in a final, desperate message to a friend, was a weight he could no longer bear. “The only option is to end my life,” he wrote. He had swallowed poison. By the time his friends understood what was happening, it was too late.

Two years later, across the continent in Kenya, a similar darkness fell on Dismas Mutai. His dream was a Master’s degree in London. His family had saved KSh 2.8 million—about 33 million naira—to give him that chance. But the whispers of easy money from online betting were too loud. In a storm of hope and adrenaline, he gambled it all away. Every last shilling.

“Depression is slowly taking me to the grave,” he confessed to the world on social media, his post a digital prayer for forgiveness. “Perhaps the UK was not meant for me, but just give me a chance to survive so that I can be a living testimony to many.”

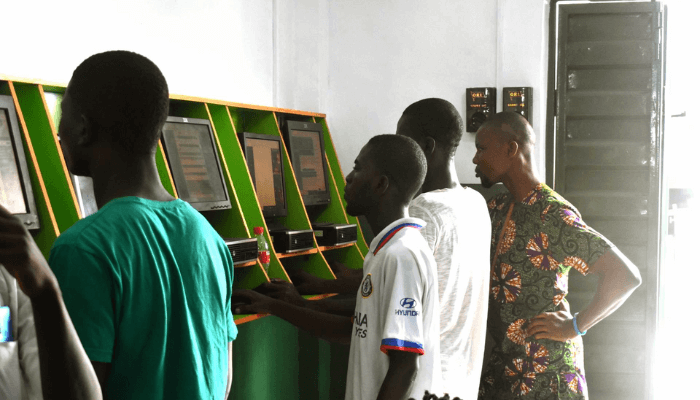

These are not just stories. They are warnings. They are the loudest alarms from a quiet and devastating crisis that is unfolding in the cybercafés, university hostels, and dimly lit rooms across Nigeria. A crisis that begins with the innocent thrill of a game but ends, for too many, in the theft of their future.

In a small, crowded cybercafé in Agege, Lagos, you can see it happening in real time. Chuka is 21. His eyes are fixed on the glowing screen, his hands trembling slightly. He is not watching a movie or talking to friends. He is watching the live score of a football match in a league he’s never heard of, in a country he will never visit. Two thousand naira rides on the outcome. To some, it is a small amount. To Chuka, it is everything. It is the hope of eating well for a day, of buying a new shirt, of feeling like a winner. It is a ticket, he believes, to a better life.

But every ticket has a price. Across Nigeria, a national fever has taken hold. What was once a casual hobby has become a multi-billion-naira industry. More than 60 million Nigerians, most of them between 18 and 40, are now regular gamblers. The dream is sold everywhere. It is plastered on giant billboards where smiling celebrities promise you a fortune. It is pushed by social media influencers who flash wads of cash. The message is simple and seductive: your big break is just one bet away.

But behind this glossy promise, a silent epidemic of mental health issues is spreading. Dr. Ifeoma .N, a psychologist in Lagos, sees the casualties every week. “We are seeing a surge in young men with severe anxiety and depression linked to gambling,” she explains. “It is an addiction that is easy to hide. A person doesn’t stumble or slur their words. They just carry a quiet, crushing weight of debt and despair.”

The cycle is vicious. The thrill of a potential win releases a rush of excitement in the brain. But the losses, which are far more frequent, bring a wave of shame, stress, and hopelessness. To escape that feeling, the gambler places another bet, hoping for the one big win that will fix everything. It almost never comes.

The numbers paint a grim picture. A 2023 study found that one in every three active bettors showed clear symptoms of anxiety. More than 40% admitted to skipping meals or ignoring their responsibilities to fund their betting.

“The thrill of the win is powerful,” Dr. Nwosu says. “But the pain of the loss is a deep, emotional wound.”

David, a 19-year-old student at a university in the south, knows that wound well. He started betting to feel like he belonged. “All my friends were doing it,” he says. “It was just for fun at first.”

Soon, it was no longer fun. It was a compulsion.

“I would stay up all night, scrolling through odds, chasing my losses. I stopped going to classes. I borrowed money I couldn’t repay. I lied to my parents. I wasn’t myself anymore.”

The breaking point came during an exam. He hadn’t studied. His mind wasn’t on the questions in front of him; it was on a football match he had bet on. He was hit by a wave of panic so intense he couldn’t breathe. That was when he finally sought help.

His story is the story of thousands of students across the country. The danger is amplified by the very tools they hold in their hands. Betting apps are marvels of psychological engineering. With their bright colors, easy payment options, and constant notifications about “hot odds” and “special bonuses,” they are designed to feel like a game, not a risk.

“This is engineered addiction,” says Tunde Akanni, a media analyst. “The entire system is built to keep you playing until you have nothing left.”

The damage ripples outward. It is not just about mental health; it is about stolen futures. Students report failing grades and a loss of interest in their studies. Temitope, who is 24, had to drop out of university. He had gambled away his school fees. “When you are always broke and stressed, you start to hide from people,” he says. “You lie. You lose respect for yourself. You lose who you are.”

To fight this, pundits believe authorities must do more than just tell young people to stop. They must treat this not as a personal failing, but as the public health crisis it has become.

According to them, “The schools must teach financial literacy and the realities of gambling addiction.

“Our government must enforce stricter rules on the misleading advertisements that paint betting as a glamorous lifestyle.

“Families must create safe spaces for open conversations, free from shame, so that a young person who is struggling can ask for help before it’s too late.”

In a country with growing economic hardship, the lure of easy money is stronger than ever. Young people are turning to betting not just for fun, but out of a desperate hope for survival. But the game is rigged. The odds are always stacked in favor of the house. And too often, the price of a ticket is a young person’s peace of mind, their potential, their future.

“If we do not act, the cost will not be measured in naira lost. It will be measured in the bright, promising futures that are being gambled away, one bet at a time,” said Dr. Nwosu.

•Onwumere is Chairman, Advocacy Network On Religious And Cultural Coexistence (ANORACC)

Photo credit: online

Inset: Onoh Chukwuma Richard

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!