A few months ago, we were at table having breakfast after Mass as we always do, and discussing the current affairs, with the usual talk about Trump, North Korea, Kenya and all the usual stuff, when Father Nouveau, our confessor, decided to tell us a story that was told in good humour but left me in a sombre mood.

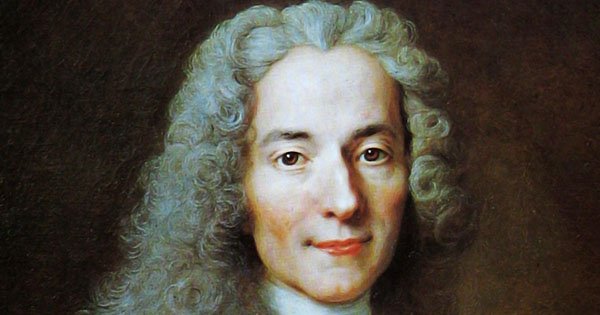

It was about the death of one of the foremost skeptics of his time, a man of acclaimed wit and lauded literary skills, a name well-known in literature more than 200 years after his death: the poet cum playwright François-Marie Arouet, otherwise known as Voltaire.

The story Father Nouveau told went a bit like this, in my own words…

When he was a young man, Voltaire and his companions, who considered themselves enlightened beyond the superstitions of their age, decided, in a bid to prove their loyalty to reason, to make a pact with each other to hold their skeptic beliefs till death and, when the time came for them to pass on, to refuse the last sacraments of the church (called The Anointing of the Sick) which are administered to the dying in order to vouchsafe the forgiveness of sins and avoid eternal damnation. According to this oath they took, the colleagues of the dying friend would stand guard around his deathbed and at the door, so that, in the event that he was overcome with fear of what lay in the next life, and the fear of hell, and called for a Priest to reconcile him to God, they, who would be sound in mind, would prevent this from occurring and thus safeguard the integrity of the oath and of their dying friend’s loyalty to reason.

On his return to Paris, 25 years after he had left to see Europe and engage his literary flair and meet people of like mind, Voltaire fell very ill, so ill, in fact, that he feared he was going to die.

Overcome by fear, he sent for a priest.

When the priest arrived at his deathbed and recognised Voltaire, he made him promise to recant his beliefs (that some claim were outright atheistic) in the event that, by God’s mercy, he recovered his health and did not die. Voltaire promised to do so, and the priest administered the last sacraments, soon after which the sick man recovered and was soon up and about again.

Voltaire, however, having survived the scare of death, and his vigour returning, refused to keep his promise and recant his beliefs, and was soon back in the company of his old friends.

A while afterwards, however, he fell very ill again. This time certain that he would die, and, again overcome with fear of the fate of his soul, he sent for the same priest again, in order that he might receive the sacraments and be reconciled to God. The priest came and rebuked him for not keeping his promise, and made him vow again to renounce his skepticism and abandon the company of his old friends were God to grant him his health a second time. Voltaire promised to do so and received the sacraments.

Soon afterward, he got better and was soon back to see his old friends.

Voltaire fell ill a third time. He was in such a horrendous state that all his friends were sent for, being informed that they would probably never see their colleague again. They flocked to his bedside and filled the room. In a brief period of lucidity, Voltaire awoke and, fearing that he was going to die, told his servant to go and fetch the priest, and lay back down again to rest. When he awoke again, the priest was nowhere to be seen and, as Voltaire wondered why he had not yet arrived, he suddenly looked all about him and saw the faces of all his friends looking pitifully down at him. And in that moment he knew the priest was not coming. He knew his friends had kept the oath. They would not permit him, succumbing to the human weakness that is the irrational fear of hell, to abandon reason at the final moment when he was so close to a victory for rationalism. No, they would keep the integrity of their friend, as they knew he would have done for them.

And so passed Voltaire.

In Father Nouveau’s own words, “he died hopeless.”