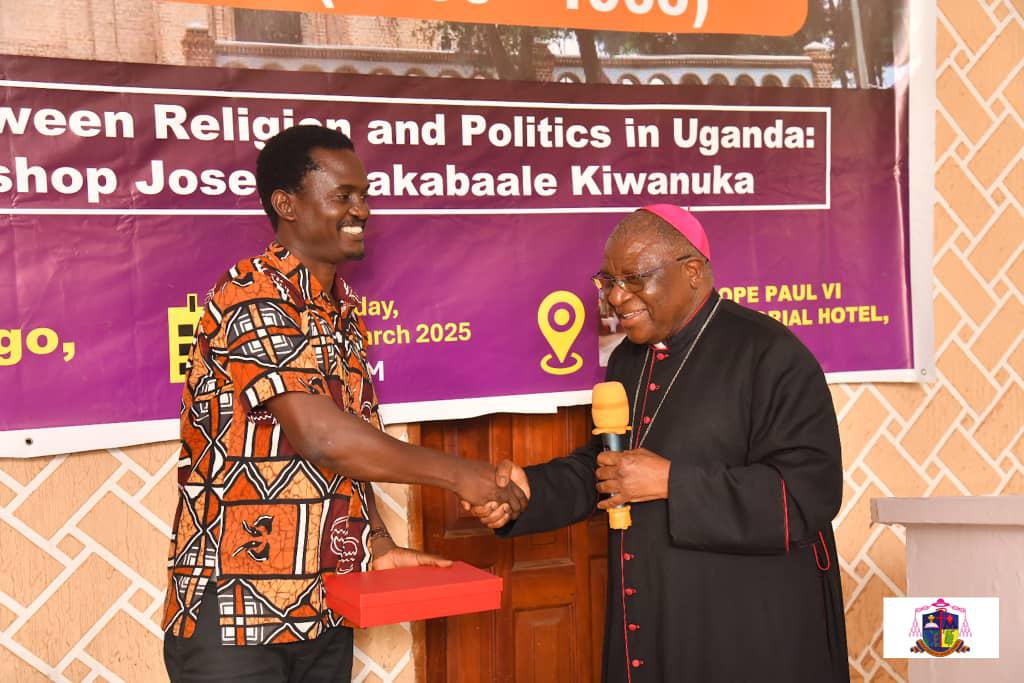

Archbishop Joseph Nakabaale Kiwanuka Memorial Lecture delivered on 6th March 2025 at Pope Paul VI Memorial Hotel-Ndeeba under the theme: “Religion and Politics”

When I accepted the invitation to give this lecture, and was still figuring out what exactly to talk about the lessons from Archbishop Joseph Kiwanuka, of course what immediately came to mind was his famous (and perhaps controversial) pastoral letter of 1961, Church and State: Guiding Principles (which needs no introduction). I had read it selectively before, without much attention to its context. This time I had to read every sentence carefully. With the benefit of having read it now, I must say that the invitation to speak here was providential. What took me this long to witness the wisdom and courage of the man? The little hesitation I still had was cleared by this letter. Where I feared as a layman that I might come across as heretical, I discovered that the things I was hesitant to say had already been courageously said by Archbishop Kiwanuka in ink. Should anyone fault me for saying anything here, I will quickly seek safety in reminding them that ‘even Archbishop Kiwanuka said it’. I will quote him, and I will even take some liberty to make him say more than he directly said.

In exploration of the lessons we can learn from him on the delicate matter of how to tread the path of religion and politics, I will rely on some of his own writings, commentaries, and testimonies. To appreciate Kiwanuka’s political contributions, one needs to understand his times and be able to picture, for instance, what it could have been like for a cleric to engage the Kabaka or a president, and the sensitivity of the matters of contention at the time. This is not a simple thing to do, because, whenever we look far backwards, we are always influenced by our own circumstances and inability to perfectly appreciate what we never experienced. Therefore, while I may have had access to some primary materials of the time, I make no claim to a very proximate understanding of them. Let this be mostly taken as my interpretation of his ideas and work, not a representation of what he would think today. Even when I directly quote from his works, I am aware that I quote what helps me to make the point I want to make. I do not want to take undue advantage of the fact that he has no privilege of reply.

The good thing with analysing the contributions of someone who is dead is that they can no longer contradict themselves. Secondly, we have the benefit of what transpired after their lives to tell whether they were vindicated or not. Some of the things for which we celebrate Archbishop Kiwanuka today, are the very things for which he was ridiculed and dismissed in life. The overarching lesson from this though is to always not simply aim at being right or correct for the moment, but for posterity. I will attempt to bring this lesson to the context of religion and politics.

What is politics; what is religion?

The most commonly cited Bible verse when the question of religion and politics arises, or when a leader from either of the domains says what the other doesn’t want to hear is: Give unto Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and give unto God what belongs to God (Mark 12:7). Jesus was responding to the rather cynical question of whether people should pay taxes or not. In choosing not to speak directly in his response, he left us with a problem of interpretation, and with an opportunity to exploit the statement. That is why we tend to privilege the interpretation that suits our purposes at the time. When a religious leader says what a politician doesn’t want to hear, he is interfering with Caesar’s work. When he is dancing to the tune of those in power, he belongs to Caesar.

It is therefore important to ask;

- What belongs to Caesar?

- What belongs to God?

- Are there things that belong to Caesar but not to God?

- Are there things that belong to God but not to Caesar?

- Who chooses Caesar, and to do what?

I will keep coming back to these questions as I attempt to engage them along my presentation.

To be able to understand the ideal relationship between politics and religion, we need to first understand what each of the concepts means. It is from this understanding that we can then ascertain the role of a religious leader and that of a political leader. Only on these grounds can we be able to lay down ideals on how the two domains and their leaders ought to relate – what they should or shouldn’t do.

From a very generic sense, religion denotes “a system of spiritual beliefs, practices, or both, typically organised around the worship of an all-powerful deity (or deities) and involving behaviours such as prayer, meditation, and participation in collective rituals” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2018). While I recognise that religious expression could be organised around groups with leadership or not, for the purposes of this paper, I will mainly focus on organised religions – since they have been more involved in the contention with politics. Since religion primarily facilitates worship of a deity or deities, religious institutions and leaders are tasked with inculcation and enforcement (for lack of a better word) of faith and behavioral norms as provided for in their scriptures and doctrines. In the case of Judeo-Christian religions, we may talk about the Ten Commandments as the centre of teaching. Indeed, even if we expanded the scope to indigenous religions, there would still be a lot in common. Reflection on these core values is important for answering the question: What belongs to God?

We are aware though that even when they may all confess to believe and serve the same God, religions may often differ in method and interpretation of the same scriptures. This has led to some clashes in the past, with terrible consequences. We also know that some religions disagree with each other’s teachings and practices. This therefore means that social order has to be regulated to permit freedom of worship, for as long as it operates within parameters that are mutually respectful and devoid of harm to others. Thus, even though religion may claim divine authority, it needs secular authority to regulate it. For the fact that religions are built around deeply emotive beliefs that are often non-negotiable and sometimes with no room for reason, religious expression may sometimes take directions that do not foster co-existence. For this reason, my presentation will not limit itself to how religious leaders should guide politics, but also how secular politics should guide religion. I will only be more inclined to the former because my case is Archbishop Kiwanuka.

Let me now turn to the notion of politics, which is also a very broad one, often used to relate to the dynamics of negotiating power, involving its acquisition, execution, and sustenance. In this sense, we can as well talk about politics in the family, at workplaces, and in the church. There is therefore need for specificity. For the scope of my talk, politics is limited to activities that relate to influencing the actions and policies of a government or getting and keeping power in a government. In the context of government, we need to pay attention to where political authority comes from. This is how we can best understand what belongs Caesar.

The question of the origin of political authority goes far back in philosophical scholarship. Many of us may take it for granted today, but shouldn’t we always ask ourselves how a few people came to have so much power over the masses? For, as the French Philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau observed, we are born free, only to realise that we are everywhere bound in chains. We have to obey laws, we have to pay taxes, we need travel documents, we can be punished with imprisonment, we need driving permits, we can’t fish as we wish… It is a long list of dos and don’ts. Where did Caesar get all that power from?

Of course, without having to go back into the history of government, we know that political authority is variously derived, depending on the arrangements that hold in a given setting. Nevertheless, it is widely agreed around the world today that political authority ought to be derived from the people over whom it is exercised. It is supposed to be from their consent and for their service. We only establish government in order to avoid something worse than it. We surrender some of our liberties in hope for some collective and individual benefits in return. We do not simply surrender to government out of weakness. Therefore, what ‘belongs to Caesar’ is strictly not his. It is only in his or her custody. The beginning of abuse of this social contract is when Caesar starts to think that power literary belongs to him.

If for some reason we risked losing the Bible, and we asked politicians which part we should save first, I am sure they would agree to save Romans 13:1. It says: “Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established.” Of course, every leader will want to remind the led that leaders come from God. It is often used as a subtle way of blackmailing the led into not questioning the authority of leaders. Citing this verse without talking about the responsibility of leaders as laid down by the same God is psychological manipulation. If leaders (secular) admit that they come from God, then they are bound by God’s law, and it is therefore within the mandate of religious leaders to guide them too. It is not necessarily interference.

I would want to add the popular Latin saying that Vox populi, vox Dei (the voice of the people, is the voice of God). However, I know from experience that sometimes the voice of the people, even in their majorities, may not be the voice of God. Nevertheless, I want to take it to mean that the saying simply intends to emphasise the importance of serving people – which should be the measure of the value of political power.

In Church and State, Archbishop Kiwanuka explicitly dives into the above debate on the role of political leaders and how the authority of the Church ought to be understood. I am amazed at how he didn’t mince his words despite the political tension at the moment. He wrote:

The State must recognise that it is also bound by the laws of God. Civil rulers have a duty to remember that God is the Authority above them, that He Rules over everybody on earth and in heaven. They must relate all their activities to Him, and in the exercise of their governmental duties, God is the Rule which they have the obligation to follow. Therefore, if a ruler, even when engaged in State duties, neglected to concern himself with religion, he would be openly violating God’s law, and would thus refuse to achieve the end for which God created him as well as that for which He created the country that the ruler is governing (1961, p.11).

In simple terms, what he is reminding civil leaders is that it is not enough to claim to be divinely anointed without seeking to operate within the provisions of the divine. One cannot be sent by God to do what is contrary to God’s wishes. Certainly, this argument can be extended to ask: “Why does God keep leaders in positions of authority even when they defy him and cause so much suffering and death to the people under them?” It is at this point that I have to declare that I am not a theologian. I can’t pretend to have an answer to the above question, especially an answer that would not trigger more and more questions.

The political circumstances of Archbishop Kiwanuka’s time

Archbishop Kiwanuka’s contributions in general and in specific reference to our topic today can be best understood when placed in the context of his times and personal circumstances. The Chinese say that “anyone can sail a ship when the sea is calm”. We need to get an idea of the state of the sea in Kiwanuka’s time.

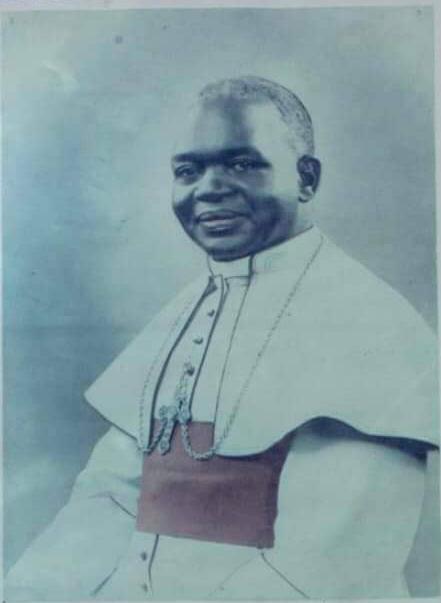

Generally, his time as bishop, and later as archbishop, can be summed up as that of being on trial. First, being the first black bishop on the African continent, and being so for 13 years, all eyes were on him. While he had to do so much to disprove the racial stereotypes about black people and therefore build Rome’s confidence for more native bishops to be consecrated, it also meant that any mistake on his side would be costly. It would have raised generalised doubts. Indeed, at his consecration as bishop of Masaka in 1939, Pope Pius XII had alluded to the massive responsibility that had been bestowed upon the pioneer black bishop:

The success of your Vicariate will be considered success for the entire Continent of Africa and will be followed by numerous local Churches led by African Bishops, while your failure will mean delay in the advancement of the Church in Africa… The people who today celebrate your being raised to this office are eagerly waiting the results of your work” (Pius XII, 1939).

To be safe, he would therefore have chosen to avoid matters that were potentially contentious, and that could have ended disastrously. National politics would have been one of those.

Why would a cleric at the time have chosen to avoid politics for their own peace? We are looking at the decade before Uganda’s independence and immediately after independence. The decade leading to independence was characterised with contestations and negotiations around issues to be sorted before gaining self-determination. The first decade after Independence was also tumultuous, carrying forward many of the preindependence controversies to explosive heights. I will briefly point out some of the outstanding events and contentions.

Religion had been a controversial part of pre-independence politics, with each of the religions trying to have a bigger influence on the Kabaka and Buganda Kingdom. This caused a lot of friction from the last quarter of the 19th Century up until independence and beyond. The height of these conflicts can be sighted in the religious wars and the killing of the Uganda Martyrs. Muteesa II had inherited some of these challenges. In some cases, he tried to neutralise them, in other cases he exacerbated them. At the time of his reign, Anglicanism was triumphant, with regard to political influence. The Kabaka himself was Anglican. In his book, The Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, Kasozi draws for us a picture of religious representation in Buganda’s leadership:

The Buganda royal family became Anglican. From 1900 to 1955, two out of three ministers at Mengo were Anglican and one was Roman Catholic; of twenty county chiefs, eleven were Anglican, eight Roman Catholic, and two Muslim; of eighty-nine members of the Lukiiko, forty-nine were Anglican, thirty-five Roman Catholic, and two Muslim (1994, p.65).

Earlier, in 1953, Kabaka Frederick Muteesa had been exiled to Britain, causing so much anxiety and tension in Buganda. It should be noted that, by then, the Kabaka was the strongest political figure in Uganda. We are told by Fr Waliggo that Muteesa and Bishop Kiwanuka (then bishop of Masaka) had been friends and remained in cordial correspondence even when the former was in exile. He was also involved in the negotiations for the Kabaka’s return, as part of the Hancock Commission which drew up the 1955 Agreement. It is after 1955 that their relations started limping, especially because Kiwanuka did not keep quiet when he felt that it was his duty to speak.

In Buganda, Catholics were more in number among the population, and they felt discriminated against. Naturally, they continued agitating for more representation and political influence. One of the key moments of tension were the 1955 elections of the Katikkiro. Among the three candidates, two were Anglican, while one (Matayo Mugwanya) was Catholic. When Michael Kintu, an Anglican won, Mugwanya was not even allowed to take a mere seat in the Lukiiko – something that displeased Bishop Kiwanuka. Moreover, Catholics felt that Muteesa had directly conspired to fail Mugwanya on the basis of religion (Muscat 1984; Kasozi 1994). It is in this context that the Democratic Party (DP) was born, as a predominantly Catholic political party. Mugwanya would later become its President in 1956. The joke that DP stood for Diini ya Paapa was perhaps an overstretch, but not far from the truth. As such, DP was born as an afront to marginalisation from Mengo. It emphasised the unpopular view at Mengo, that the Kabaka should stay out of partisan politics, and that Buganda becomes a constitutional monarchy.

When the Kabaka returned from exile in 1955, on his visit to Buddu, Bishop Kiwanuka, who had mobilised Catholics to pray daily for his return, now used the opportunity to politely express discontent. He said:

Our most beloved Ssabasajja Kabaka, I stand here in the holy place, the seat of Catholicism in Buganda and Uganda as a whole. I stand here to welcome you and congratulate you in the name of all Catholics. Ssabasajja thank you, thank you so much for achieving victory! You are our victorious warrior! They snatched you from us secretly, we never bid you farewell. For two full years you were out of our sight. That is why today we are overjoyed! If our eyes were able to devour, they would have devoured you today! You are an excellent Commander-in-Chief. You led us well and you never turned backwards.

We, your subjects, who remained here, fought likewise. I do not know whether you will ever be able to find out what role Catholics played in that struggle, given the fact that they rarely get a chance to be among those who keep by your side. When you get time, however, to penetrate the cloud, you will discover that among your subjects none love you more in truth, without self-seeking motives, as the Catholics. You will then know that in the struggle for your return, none fought as fiercely as the Catholics.

Some acted as a security for you, some became hated on your account. You will also discover that none played such an active part in keeping peace in the country as the Catholics. Catholic leaders preached peace everywhere and people obeyed. You know well that of your people who are over a million, almost half is Catholic. To keep such large number calm was not a minor job. If they decided to become rebels, the entire country would have been disturbed.”

In the Legislative Council (LegCo)elections that preceded Independence, Buganda chose to boycott. DP, led by Ben Kiwanuka, a staunch Catholic, participated in the elections. To the Kabaka and Mengo, this was betrayal. In his autobiography, Desecration of my Kingdom, Muteesa notes that DP “were seen as traitors to Buganda, trying to grab office at the expense of loyalty. DP became and remained the most insulting of swear words” (p.136). In fact, so bad was the rivalry with DP that Muteesa confesses that it is the worry about DP that could have led him to go astray in the politics that led to his second exile.

In his Pastoral letter that was issued in November 1961, during the heat of the LegCo elections, Archbishop Kiwanuka supported the elections, defended the view that Buganda should be a constitutional monarchy, and condemned the extremism of Mengo’s Kabaka Yekka party. He directly advised Catholics to stay away from Kabaka Yekka, which he said was neither registered nor with a manifesto. This was seen by Mengo and many loyalists as ‘looking the Kabaka in the mouth’. Mengo packaged any view opposed to theirs as being ‘anti-Kabaka’. Earlier, in August 1961, Kabaka Yekka had issued a pamphlet where they stated their position with regard to the Kabaka and legislation. They asserted: “… Nobody can ever have a superior position over the Kabaka on Buganda soil, also in Buganda no one or body of people can ever make laws for the Kabaka’s observance, and it is contrary to Buganda’s traditions for any person or group of commoners to make a law which the Kabaka is expected to observe” (28th August, 1961, cited in Low, 1971). This meant that the Archbishop had challenged the Kabaka. Indeed, the Archbishop’s letter almost caused his arrest by Mengo. Since he wasn’t in the country, it was his Vicar, Msgr Ssebayigga, who was briefly held.

Up until Archbishop Kiwanuka’s death in 1966, the same year that the Kabaka was deposed and exiled, the relations between the Catholic Church and Mengo remained tense. So much so that on one occasion, the Archbishop narrates in his Letter, when he visited Bulange, he was jeered by a mob. A man danced in front of his car, shouting, “from now on your religion will find no where to stand”. Nevertheless, fate is so stubborn sometimes. When Kabaka Muteesa was desperately fleeing upon Obote’s attack on the Lubiri, his first stop was at the White Fathers’ residence. Here is how he narrates it:

Two taxis driving without particular urgency came into sight… We clambered in and asked them to drive us a couple of miles to the White Fathers near the Roman Catholic cathedral… The Fathers received us, calmly accepting the unfamiliar clatter of rifles on the refectory table with aplomb… Sloan’s liniment was produced and my back rubbed… We spent part of the night there… (1967, p.7).

It is said that one of the priests the Kabaka spoke to while there was Emmanuel Nsubuga, and that he asked him: “keep my kingdom”. This parting gesture was a mark of trust. As I turn to the lessons we can draw from how Archbishop Kiwanuka negotiated his political circumstances, one clear message demonstrated already is that, when you stand for the truth, politicians may not like it, but they will internally respect you for your principles. They do not honestly respect those that they can manipulate.

“I cannot remain silent”: What lessons for us today

While Archbishop Kiwanuka was vilified in some circles while alive, he was vindicated only a few months after his death. He had earlier ended his Pastoral letter with a warning:

… I hope that many who were blindfolded will be grateful to me and will be pleased to see that I have brought to light the snare hidden in the ground which was invisible to them; now if anyone wants to tread on it and is caught in it, everyone will be able to tell him: “After all, you trod on it while you saw it clearly” (1961, p.29).

Indeed, the snare soon exploded, rather disastrously. As we diagnose what happened then, and what could have happened differently, it is critical to as well pick what can be learned. From the side of Kiwanuka, I will start with what he chose for the second subheading of his Pastoral letter. He titled it: ‘I will not remain silent’.

Kiwanuka could have chosen to remain silent amidst all that was happening at his time. The stakes were quite high for a cleric, let alone, as I noted earlier, that any mistake of his would be costly to the Church in Uganda and black Africa. He chose not to remain silent. I will repeat this, he chose not to remain silent. This is not to say that all his engagement with political leaders was through open speech. There is indication that he as well engaged in ‘behind the curtains’ diplomacy. I also do not intend to undermine complete silence as method. Che Guevara tells us that ‘silence is speech by other means’. I’m also reminded of a scenario at Uganda Martyrs University, when a colleague accused the Deputy Vice Chancellor, the late Fr Dr Kisekka Joseph, of remaining silent about a certain policy that staff had expressed concern about. Fr Kisekka responded that, “If you do not understand my silence, you will not understand my words either”. That’s all he said about it. The problem with silence though is that it doesn’t directly say what it wants to say, and therefore remains open to multiple interpretations. Using it alone is therefore not advisable. It is insightful to carefully study Archbishop Kiwanuka’s choice of methods of engagement in the different circumstances, and his deliberate efforts at moving along with his people so that they know what was going on and where he stood.

We have argued elsewhere in a journal article I co-authored with Henni Alava on Religious depoliticisation during the 2016 elections, that while the diplomatic (behind the curtains) approach is at times more effective, it comes with a danger of eroding public trust in religious leaders. The public is left to guess what is happening, often suspecting cowardice, indifference, or being compromised. Baganda say that kigumaaza, nga ente esula mu kyooto. Bwowulira essa ogamba nti ekumamu (as confusing as a cow that sleeps by the fireplace. When you hear it breathe you may thing it is lighting fire).

Silent diplomacy, as the consistent method of choice, becomes even more suspicious where at the same time people see government or politicians handing over huge ‘gifts’ to religious leaders. It is in this context that one appreciates the importance of not only engaging, but also being seen to engage, so as not to send mixed signals to the public. In any case, the suspicions created by silence are not good for evangelisation either, since they discourage some people. Recently, on Janan Luwum Day, a joke made rounds on social media. Someone tweeted: “I went to Church today. I was about to give tithe. But when I remembered that my bishop had not said anything about Besigye’s unfair detention, I said to myself: ‘Let government give them the tithe’”. While this might appear to be a mere joke, I think that how religious leaders respond to the afflictions of their people goes a long way in influencing their faith or lack of it. When Catholics were being persecuted by Kabaka Yekka, Kiwanuka boldly stood with them, the risk notwithstanding. He candidly took on a prophetic role.

After Kiwanuka’s death, on many occasions, some religious leaders and umbrella bodies have been outspoken against undemocratic practices and they have sometimes come out to suggest alternatives. The response of the state has mainly been five-fold: Sometimes it has been dialogue; sometimes silence; sometimes violence; sometimes reminding religious leaders that it was not their business; and sometimes it has been material inducement.

On gifts to clergy

I will dwell a bit more on material inducements since they have been one of the biggest challenges of the post-Kiwanuka time in regard to the relationship of religious leaders and politicians, and in shaping agency. The phenomenon of ‘gifts’ is not new to Ugandan politics. It appears that all presidents understood the old saying that: ‘No matter how far an eagle flies up the sky, it will definitely come down to look for food.’ President Milton Obote, an Anglican, had a lukewarm relationship with the Catholic Church under Archbishop Joseph Kiwanuka, especially following his government’s move to take over church schools. When Archbishop Kiwanuka was succeeded by Emmanuel Nsubuga, Obote saw this as an opportunity to mend fences with the Catholic Church – since even the Protestant group had split into two factions, one supporting Obote, another sympathetic to the Kabaka that had been overthrown by Obote. At a church service at Rubaga Cathedral, Obote personally handed over a present of a Mercedes-Benz to help the Archbishop with his duties.

Professor Kasozi (1994) notes that when Amin took over power from Obote in 1971, having observed the challenges the latter faced from religious leaders, he was initially keen on creating an impression of a religious pacifist, or, as some called him, an ‘ecumenical mediator’. He soon created a Department of Religious Affairs and organised religious conferences in 1971 and 1972. He as well persuaded the various Muslim factions to work under one body – The Uganda Muslim Supreme Council (UMSC), and urged Anglican factions to as well unite. He often consulted and sought the company of religious leaders. One striking gesture is when he was accompanied by the Muslim Chief Kadhi, plus the Catholic and Anglican Archbishops to the OAU summit in Morocco in 1972.

On 31st December 1971, Amin’s government donated 100,000/- to the Muslim, Catholic, and Protestant faiths, each. He also donated 12 acres of land in Old Kampala for the construction of a mosque and headquarters of UMSC. Towards the project of constructing the Catholic Martyrs’ shrine at Namugongo, he donated his salary. Outdoing Obote in car donation, he gave each of the three religious leaders a Mercedes Benz.

Later during Amin’s leadership, seeing that there was still resistance from religious leaders towards his excesses, he gradually replaced donation and consultation gestures with threats and violence. Where the carrot fails, the stick often follows. While it is the murder of Archbishop Janan Luwum and Fr Clement Kiggundu that took prominence, several others were killed, including Muslims who either resisted or seemed to stand in his way.

Donations to religious leaders have taken interesting new twists under President Museveni. At almost every consecration of a new Catholic or Anglican Bishop, a car has been donated by the President. The first time I witnessed such presidential car donations was as a little boy at the consecration of the late Bishop John Baptist Kaggwa of Masaka. It was a Pajero. Looking back at the work of Bishop Kaggwa now, I don’t think the gift achieved much.

Some not only get car gifts but also the privilege of convoys with military escorts. The irony is that there has been no public report of any of the clerics seeking to establish the source of funds for the random cars that are never accounted for. I imagine that it is conveniently assumed that the source must be the official presidential budget for donations. Besides, and for more convenience, isn’t it impolite to look a gift horse into its mouth? The German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche asked: “Shouldn’t the giver be grateful to the receiver?” Indeed, the President must be grateful.

In 2013, Muslim leaders in Luwero district expressed discontent with the President for side-lining them in his donation of vehicles and other things to religious leaders. In 2015, the President donated cars to eleven Muslim district leaders. Shaking hands with him while receiving the car keys, they chanted: “Allahu Akbar”. In a more dramatic case, in 2023, Christians in Kigezi complained on behalf of their Bishop that the car which had been donated to him at his consecration was inappropriate. Two months later, a Toyota Land Cruiser GR-Sport was delivered in replacement, and the Bishop thanked the president for listening to the concerns of the Christians.

The peak of the car phenomenon could have happened last year (2024). In front of cameras, and other religious leaders, an Anglican bishop humbled himself and laid his request in the following words:

My lord the President, after this prayer, if you permit me and I convey my words to you through your Private Secretary, my car is worn out. It will not handle 2026, yet you know we are approaching 2026 [year of elections]. God bless you.

After watching this video, someone quipped on Facebook: “Kati abasumba twabavaako bakola byebaagala” (now we gave up on the clergy and left them to do whatever they want).

These gifts remind me of a certain government official whom I drew in a critical cartoon and he reached out to me commending me for it. He requested to buy a framed copy of it, for which he gave me more money than I charged him. I know how it feels criticising him again, and therefore understand when concern is raised about the random gifts to religious leaders. It is not helped by the fact that many beneficiaries go quiet or vague after. There have been some exceptions, but certainly these gifts complicate the prophetic work of the clergy and raise suspicion among believers. It may be argued that religious leaders complement government in serving people and therefore deserve being facilitated. However, even if this were so, the facilitation shouldn’t be arbitrary, because that attracts abuse and patronage. Should religious leaders reject the cars then? I think the answer to that question is by asking oneself: “What would Jesus do?”

On the other hand, with reduction in foreign funding to religious institutions, many have found themselves at crossroads – where government or politicians are the main patrons, since much of the money is now in their hands. Added to the huge construction projects that many religious institutions have undertaken in the recent past, plus a growing public culture of fundraising, no one wants to annoy the ones with money. For we shall want to invite them as chief guests at our fundraising events, and they’re the ones that add weight to offertory baskets. How do we call them out for the rampant corruption, nepotism, and inequalities! How do we question the source of their immense wealth? Recently, a politician from one of the national institutions that have been all over the news with horrifying accountability concerns, donated a fully constructed church worth billions of money. It was received in jubilation, pomp, and praises – no accountability questions. What would Archbishop Kiwanuka have done? Should the tables of those trading in our Father’s house be overturned with the moneys on them? It is a challenge that religious leaders need to carefully reflect about. Accepting to benefit from what could be proceeds of theft from the poor is a tacit endorsement of the theft. We cannot condemn something yet be happy to benefit from it.

Meddling in politics?

It is common for religious leaders who call out injustices to be advised by politicians to stick to their work and not meddle into politics. It is not a new method of silencing, Archbishop Kiwanuka dealt with it too. He addresses the matter in Church and State:

Time and again I have heard such things as “keep religion out of politics, leave religious ideas out of politics…” Among those who speak like that, some do it out of pure hatred of religion. It could not be explained otherwise since in fact religion strives to remind people of their duty to serve God, which in no way harms politics. On the contrary it is a real help to it. But there are others who are induced to say that they don’t want religion to be mixed with politics by the mere fact that they are afraid of the truth and justice inherent in religion. They would like to deceive people in order to bring them to their side, but religion helps people at the time of choosing a government to see objectively what is right and to choose a good government. There are finally many people who repeat “keep religion out of politics” without any understanding whatsoever of what it is all about. (1961, p.10).

At the 16th Coronation anniversary of Omukama Solomon Gafabusa of Bunyoro in 2010, President Museveni used the analogy of Olubimbi (digging allocations) to demonstrate that politicians, religious, and cultural leaders each have their role. In a subtle threat, he said that if one suddenly abandoned their lubimbi and crossed into another person’s, he/she could easily have his head cut off and become a casualty. “I have never baptised anyone, though I know how they baptise. I am a Christian but I do not baptise—that is not my role”, he added.

Ironically, religious leaders who actively join the government side are welcomed with open hands, and some are directly appointed into political positions. It is possible that, following the constant reminders to not trespass, out of fear, some religious leaders have in selfpreservation decided to either tread very carefully, withdraw from politically sensitive matters, or operate on an evasive level of generality – such as in making blanket calls to all Ugandans to be fair to each other. Besides, there is also the awareness that being seen as a critic of government can come with other survival costs to religious institutions and individual leaders. Some religious leaders have raised concerns about spies being planted amongst them and divisions being sowed in their spaces in ‘divide and rule’ strategies.

There is as well an emergent category of churches built around individuals. Without national and international structures, they know they are more vulnerable than their institutionalised colleagues. They can be very easy targets of state repression. Some of these have carefully studied aspects of existential desperation in the country and constructed their religiosity around those – poverty, relationship challenges, unemployment, disease, etc. With promises of spiritual and mystical intervention, they financially exploit their followers. Because the state can always find good reasons for closing them, such church leaders know that their security is either in aligning with government interests or remaining silent about government shortcomings. As the adage says, a person who sells eggs should not start a fight in the market. After all, with a few exceptions, they have observed that their ‘connected’ colleagues who have committed scandals walk away scot-free.

Conclusion

There is a lot to learn from Archbishop Kiwanuka in imagining how politics should relate with religion, especially in view of the challenges we are faced with today. The times are different, the players are different, but there is a lot that is relatable.

- There was a lot to fear during Kiwanuka’s time, there is a lot to fear today. Courage remains a crucial virtue.

- There were many injustices that needed to be spoken to then, there are so many today. We cannot remain silent.

- The church needed politicians then, the church needs them today, and vice versa. There is need for working together in mutual guidance.

There have been some significant changes too. The quality of politicians today may not be favourably comparable with that of Kiwanuka’s time. Much as populism was an issue then, I think it has escalated. The political opportunism and greed today are also unprecedented. This would ideally mean more work for the clergy to guide the masses about leadership, and to groom leaders. Religious leaders still have a voice that is widely respected, especially those that do the right thing. In Kiwanuka’s Pastoral Letter, he guided people on how to vote and what qualities of leadership to look out for. Religious leaders relate closely enough with the people to understand their character and accordingly guide the vulnerable masses. In a number of instances, unfortunately, even in the church, money has been the key determinant of who the church endorses – hobnobbing with known thieves, as long as they are generous.

Archbishop Kiwanuka understood quite well that national leadership was a critical determinant of a society’s development and quality of life. We cannot detach spirituality from material quality of life. A people wallowing in poverty cannot easily appreciate God. A life of poverty and existential challenges of poor healthcare, poor education, poor feeding and poor living conditions is very tempting. In such a life, sinning might become inevitable. It is relatively difficult to understand and extend love while living in misery. Therefore, salvation of the soul goes hand in hand with fulfilling existential needs. I guess this is part of what Jesus meant by saying that He came so that we may have life and have it to the fullest. As such, politics cannot be ignored by religious leaders without affecting the salvation mission. The complementarity of religion and politics is self-evident – both of them for facilitating achievement of the common good, and to check each other through their relative powers and obligations.

References

Kasozi, A. B. K. (1994). The Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, 1964-1985. Montreal and Kingston, London, Buffalo: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kiwanuka, J. (1961). Church and State: Guiding Principles. Kampala: Marianum Press.

Low, D. A (1971). The Mind of Buganda: Documents of the Modern History of an African Kingdom. London, Ibadan, Nairobi: Heinemann.

Mudoola, D. M. (1993). Religion, Ethnicity and Politics in Uganda. Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 1993.

Muscat, R. (1984). A short history of the democratic party, 1954-1984. Rome: Foundation for African Development.

Muteesa, F. (1967). Desecration of my Kingdom. Kampala: Crane Books.

Waliggo, J. M. (1995). The Catholic Church & the Root-Cause of Political Instability in Uganda. In Hansen, H. B. & Twaddle, M. (eds). Religion & Politics in East Africa: The Period Since Independence. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, pp.106129.

Waliggo, J. M. (1991). The Man of Vision: Archbishop J. Kiwanuka. Kampala: Marianum Press.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!