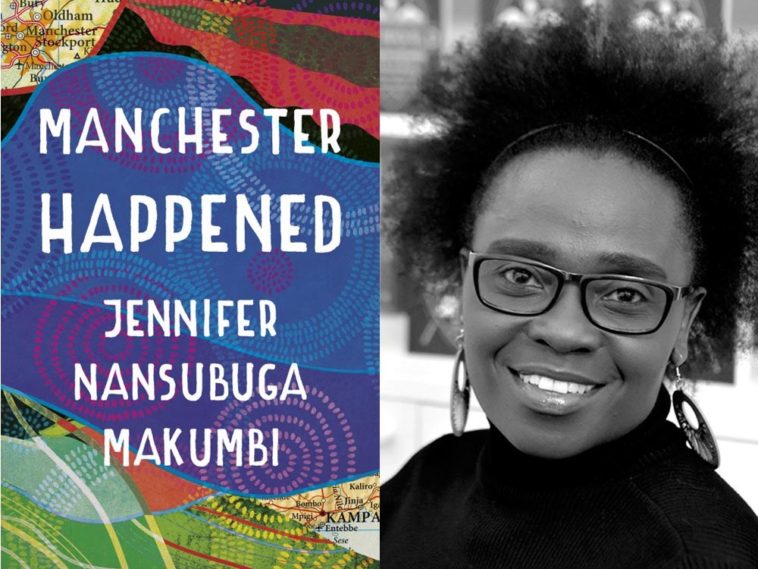

Without wasting time, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi takes us on a journey into the complexities of human nature that make up the pages in the collection of short stories, Manchester Happened. We are confronted by feelings of fear and anxiety experienced by a 13-year-old boy; feelings which we later understand to be catalyzed by shame and anger.

In the prologue, Christmas is Coming, we meet an agonizing Luzinda who unlike many 13-year-olds, is dreading his birthday. He is unusually aware of how close his big day is to Christmas, which always seems to break the demon in the house loose. It is only later that we realize that the demon he makes reference to is actually his mother’s problem with alcohol. Throughout the story, he is portrayed as the protector of his father and younger brother Bakka. Bakka, on the other hand, is the peacemaker in the household. At the end of the story, while at the Christmas party where many of the Ugandans gather, his mother’s demon emerges as she fails to control her drink. In her visibly drunken state, she insults some of the guests, including her husband and also makes a mess of herself when she topples over. It comes to light that part of the reason this demon exists within her is because her husband, previously a paediatrician in Uganda, failed to get a job in Britain, leaving her the onerous task of being the sole provider. We are left carrying the weight of Luzinda’s anger, Bakka’s actions to divert the attention away from his mother, all while questioning their father’s patience and gentle reminder to his son, “Mom loves you Luzinda. You cannot forget that.”

This body of work is divided into two parts. We are told stories of those departing and those returning whether temporal or to make sense of life in Kampala after what almost seems like the disruption that is Manchester. We are taken as far back as 1950 in Our Allies the Colonies when air travel to Europe seems like a far off dream. We encounter Abbey who “felt a rush of dizziness like life was leaving his body” because It is clear in the stories that follow, that that is what Manchester does to anyone who does not belong to Her. We see the same thing happen to Nnambassa and Katassi in the story Manchester Happened. They struggle in the beginning to adjust to life away from home even though they have a softer landing, in comparison to others who are finessed and often end up in prostitution, contracting HIV/AIDS. Clearly, life pulls the rug from under the feet of many who arrive in Britain’s cold streets.

The challenges of life that are deeply rooted in culture shock cause a rift in the relationship between two sisters. It takes their father, Mzei who is almost dying, traveling across continents in a bid to mend the relationship several years later; but all this is in vain. Manchester does that – not even blood bonds can withstand the pressure She imposes. In Manchester, Ugandans have no choice but to undress themselves of their past identities and forge new ones in order to make the most of their time there. In the story, Something Inside so Strong, all one’s wealth in Uganda does not matter when they arrive in Britain. For as long as one does not belong to Manchester, like a bad reputation, the hustle will always hunt you down. The character Poonah adequately articulates this when she says to Namuli, someone she knows from her past, that “being in Britain is the proverbial prostituting: you know you came to work, so why get in with knickers on.” This statement rings loud as a call to duty; that one has to be flexible and accepting to anything in order to survive and make money; open for business 24/7.

This chilling reality is juxtaposed to The Aftertaste of Success, a story in Part 2 of the collection. In this story, we are introduced to Kitone who returns to start her life after spending years in Britain with her father. Through her, we meet matriarch Nnakazaana whose hard headed-ness is the reason she no longer gets along with her son, Kitone’s father. Interestingly, we also meet Mikka’s parents who are filled with regret for sending all their children away and are now left a “childless, grand-childless couple” with no one to inherit their wealth. Mikka is Kitone’s best male friend who is married in Britain. Distance has led to an irreparable breakdown in the relationship between parents and their children and created a disconnect between grandparents and their grandchildren. Mikka’s mother actually describes this when she says; “to send your child abroad is to bury them.” This reiterates the idea that those who leave assimilate to new cultures/create new ways of being and living and discard the old identities. This is “the bitter aftertaste of success.”

It is evident in all her work, that Makumbi does not write for the sake of writing. I especially enjoy that she analyzes complex issues in society and uses those as reference points for her writing; so we are confronted and challenged to grapple with those issues in a different way. In a lot of ways, she gets us thinking about how we, as readers, and perhaps the rest of society portray ourselves so we can find other ways of being.

While there is much to be in awe about the stories within these covers, I found it especially difficult to read the story Memoirs of Namaaso which appears to be written from the perspective of dogs that are taken from Uganda to Britain by their owners. Perhaps the hardest part about reading this story was that I failed to connect with any of the characters. Unlike Makumbi’s other writing, I found the process of decoding this particular text tedious, especially in the beginning and this inevitably disinterested me in reading past it.

However, this still does not take away from the truth that Makumbi masterfully weaves stories together in a way that reveals the complications of life. While survival is what many of us are after, the truth is that we live multi-issue lives. From the beginning, Makumbi’s intention to give a different perspective to life is not lost. We see that it is not just men who can be drunkards, and that many mistakes, however small, can turn into a lifetime of consequences carried across generations.

Her contemporary, Yemi Aribisala, draws this out clearly in her short story, A book between you and me. She writes not only about how society continues to allow toxic masculinity, but also through the narrator, forces us to reflect on how we all play a role in perpetuating it. It is clear that as a collective, we have come to believe one side of the story. This work urges us to question; the actions of those around us and how we respond to these actions. At the most individual level, we are inevitably called to reflect in more ways than one.

We are confronted with the reality of our blindness in seeking answers from the West, chasing money at all costs, while neglecting the goldmine we are seated on. Makumbi forces us to examine our attitudes towards our country all the while highlighting the startling reality of China slowly taking over that which we are leaving behind. Her stories also make commentary on how so many of us, also still living in Uganda are adapting to individualistic lifestyles forgetting that ours is a community that is based on Ubuntu ( I am because we are).

I especially enjoy that every time I pick up her work, I am definitely going into a history and cultural lesson. This particular collection features the Ganda and Gishu cultures. She is deliberate in her choice of names for the characters throughout the stories, this is something which solidifies the setting. Embedding these stories in our history, present and future; much like Gorreti Kyomuhendo in her short story, Lost and Found published in New daughters of Africa edited by Margaret Busby.

Okey Ndibe, in his address to writers at the African Writers Trust Writing Workshop in September 2019 in Kampala said that literature is vital to what makes us human and enables us to engage in moral investigation. This collection of short stories does just that. With these stories, we are invited to sit with uncomfortable emotions; to interrogate them while making sense of them. Ultimately, we choose how to respond to them.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!