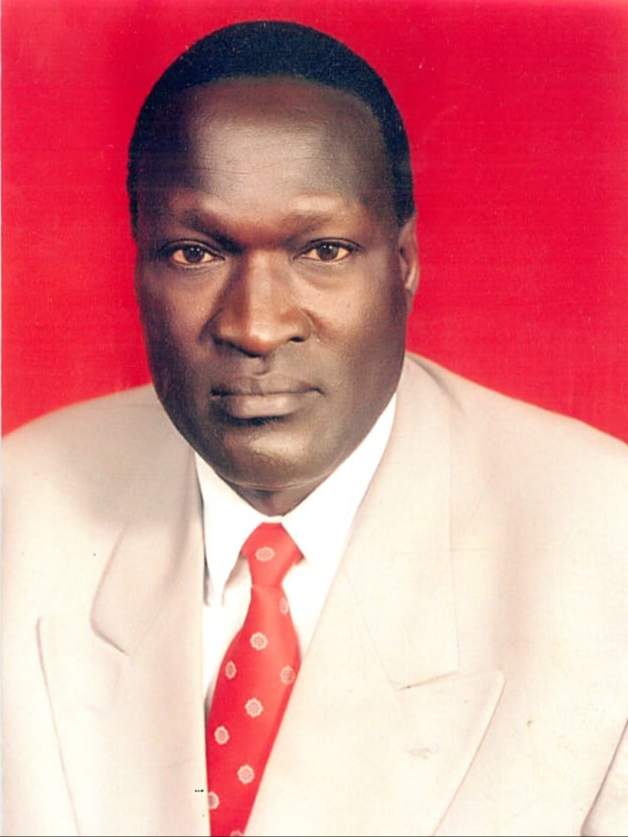

Micheal Ocan was a well-rounded individual. His idealism, determination and sense of community were elements in his character and courage as he stood on the brink of the many changes in Uganda.

He came from a distinctive generation, the generation which believed in service over self. One could say this generation incarnated the age of Ugandan innocence.

A time when leaders such as Milton Obote came up with grand designs woven in the fabric of a dream in which equity trumped inequality.

A time when Ugandans sought communal security at the expense of personal identity. This ethos carried us beyond definitions of class and tribe, region and religion. Like Michael Ocan, we were free beings.

He and his ilk had emerged from colonialism to achieve independence. Such a quantum leap from one world to the next expressed the interior strain of Uganda’s sense of human limitation and sense of possibility all at once. Uganda became a nation full of its own contradictions, coexisting within its sameness.

At the time, there was less of a breach between modern and traditional societies, collectivism and individualism. The elites at the time tended to be modern yet not individualistic. Unlike today when elites are unburdened by the collective problems of a nation in need of a collective response to those problems.

In the past, society was constructed upon the masonry of communalism. This is why African socialism was a powerful battle cry among the elite at independence.

Today, such collectivized will and thought are a distant memory. This situation invokes William Whyte’s 1956 book, The Organization Man. This book highlighted the divergence between two ethics constantly at battle in American society.

Whyte wrote about the Protestant Ethic, the idea that the “pursuit of individual salvation through hard work, thrift, and competitive struggle is the heart of American achievement,” and a Social Ethic: “of himself, [man] is isolated, meaningless; only as he collaborates with others does he become worthwhile, for by sublimating himself in the group, he helps produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

He concluded that the Protestant Ethic was losing ground to the Social Ethic.

In Uganda of today, the reverse is true. The elite are pursuing individual salvation. They have good jobs, property and are cushioned by comfortable values which extoll the virtues of individuality, continuity and stability.

Yet this has led to greater inequities with the rise of the urban and rural dispossessed. That’s why wars ravaged Uganda in the past and they shall rock Uganda in future unless we achieve something greater than themselves, at a collective level.

Yet, in a capitalist economy, the dominant ethic is individualism. This protects individual rights to preserve standards of living and earnings.

However, you shall see that in Michael Ocan’s coming of age, these materialistic considerations were immaterial. He came from a revolutionary age in which progress was context and not a pretext for one-upmanship.

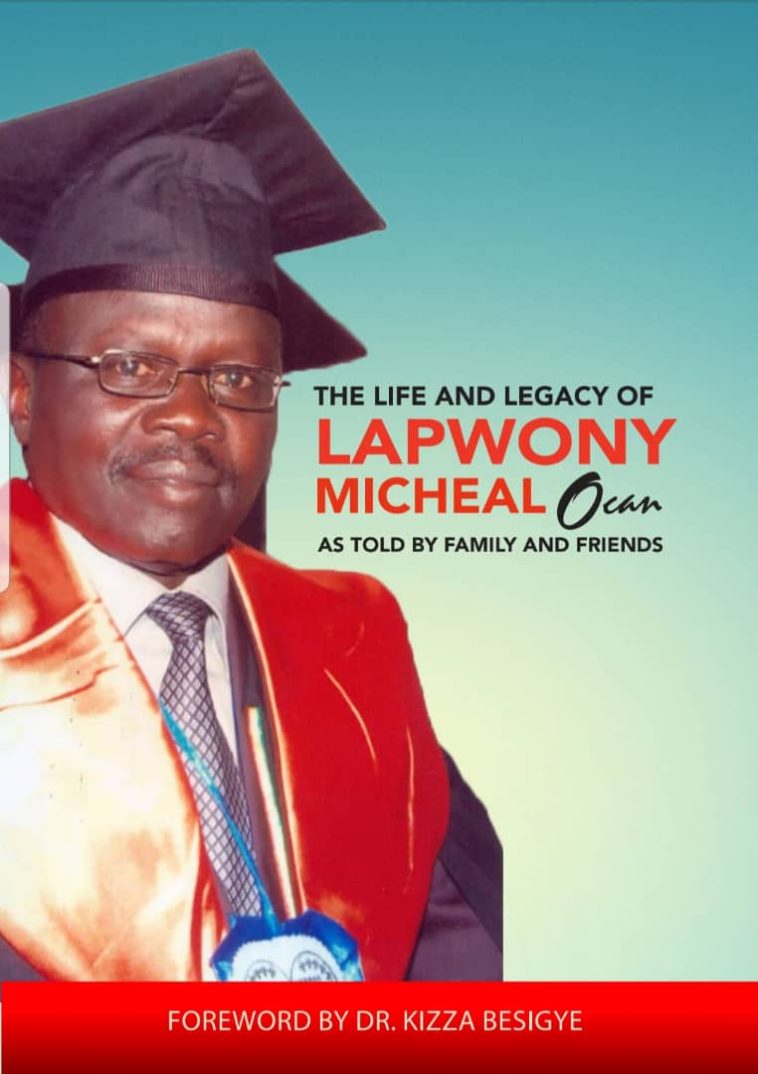

His life as a teacher at St. Joseph’s College Layibi, Gulu, is a testament to that. He taught there from 1976-84, retired as headmaster of Kitgum High School in 2014 and passed away in February 2017.

Mr. Ocan started out as a student-teacher at St. Joseph’s College Layibi during his second year at Makerere University in the 1975/76 academic year. He was posted permanently to the school, as a full-time teacher, in 1979.

His colleague and fellow teacher George Obua H.A. believes that this period was pivotal in shaping Ocan the man, the teacher and later the school administrator.

Mr. Obua said Mr. Ocan exhibited “a high level of team spirit” as he worked with his colleagues. This is the time he even fell in love with the love of his life, then subsequently marrying the only female teacher on St. Joseph’s College Layibi’s teaching staff, Ms. Aol Betty.

Mr. Obua relates, quite fondly, how the teaching staff was tightly knit with many interesting personalities namely Mr. Ojera John Charles (RIP), Mr. Okello Caxton A. Oryem (RIP), Mr. Dwokatua Vincent Uma (RIP), Mr. Okeny David Ojok, Mr. (Prof) Piwang George and Mr. Lapyem Alex (RIP).

It was certainly a motley crew of patriotic teachers who chalked their excellent teaching practice up to a singular yen for public service. While a teacher, Mr. Ocan stayed in staff house Number 14. A place he started a family with fellow teacher Ms. Aol Betty. They sired 3 children here.

“While at Layibi College, Mr. Ocan exhibited himself as a political activist and was eminent in the support for the Uganda Peoples’ Congress,” says Mr. Obua.

As a political mind, Mr. Ocan was in his element. Apart from teaching, he found his calling in politics. He was one of the young radicals who formed the Uganda Peoples’ Congress (UPC) branch in Gulu on 17th July 1980. This led to other branches mushrooming across post-primary institutions in Gulu.

His organizational talent was evident as he played a signal role in helping UPC rustle up victory in the 10th December 1980 general elections.

He was known as a kingmaker, a powerbroker unrivalled in his ability to move and shake up the political landscape.

In those 1980 general elections, UPC romped to victory in three constituencies. The winning UPC candidates were E. Otema Allimadi of Gulu East, Akema p’Ojok of Gulu West and Gulu South was taken by Y.Y. Ongwen.

Mr. Ocan was an opinion leader and political mobilizer without parallel. However, he was also instrumental in bettering the lot of his community in many other ways.

He oversaw the formation of Layibi College Staff Canteen. This, as is mostly the case with such undertakings, brought teachers together and helped them pool resources to survive.

It might be described as a precursor to today’s SACCOs. Which are owned, governed and managed by members who have the same common bond.

However, Mr. Ocan’s innovation was more collegial than a legal body registered under the Cooperative Societies Act as the SACCOs are.

Still, SACCOs and Mr. Ocan’s canteen are both considered economic institutions involved in business activities for purposes of making their members lives more conduced to trying economic circumstances.

In the 1970s, Field Marshal Idi Amin’s “Economic War” made such circumstances even more trying as essential commodities all but vanished. So one couldn’t readily get sugar, soap and salt.

Mr. Ocan’s canteen helped its members (mainly teachers) get these scarce commodities, at an affordable price.

Apart from his communitarian and entrepreneurial spirit, Mr. Ocan was also behind the formation of the Gulu Post Primary Teachers’ Association (GPPTA) and thereby helped forge closer links of interaction between and among teachers at a professional and, inevitably, a political level.

Clearly, Mr. Ocan was a pillar in a society which, like all other societies, cried out for the heroism of his stripe.

Mr. Obua left Layibi College in May 1982.

Nonetheless, he and Mr. Ocan stayed close and worked together in the Family Planning Association of Uganda (FPAU).

Mr. Ocan or “Mike”, as Mr. Obua fondly calls him, served as district chairperson Gulu for FPAU while Mr. Obua served in the same capacity in Lira. Both men were also delegates to the National Executive Committee (NEC).

Mr. Ocan’s ambitious streak and ability to get things done got him elected to the position of National Vice Chairperson NEC. He served as deputy to Dr. James Ssengendo.

One would think that such an illustrious career had reached its acme.

No, quite the contrary.

For Mr. Ocan had other notches in his belt.

The Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) was lucky to have Mr. Ocan and Mr. Obua as examiners and later senior examiners. Mr. Ocan was senior examiner for Physics and Mr. Obua, for English.

It is interesting that such a political mind was also Cartesian and clinical enough to cut to the core of scientific exactitudes. Well, such was the well-rounded nature and ability of Mr. Ocan that he was able to make sense of the dialectics of Karl Marx as well as Newtonian laws.

That’s why, even after retirement, UNEB still had work for him and Mr. Obua.

They both monitored Primary Leavers’ Exams, Scouted for Uganda Certificate Education and Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UCE/UACE).

They were both to become headmasters, Ocan at Awere SSS, Sir Samuel Baker School and finally Kitgum High School, and both also served as area supervisors for both UCE and UACE examinations.

This cemented Mr. Ocan’s credentials as an educator par excellence.

That said, Mr. Ocan’s first love was still politics. One can see from the minutes of staff meetings how political this man was.

For instance, “A Meeting To Discuss The Political Position Of The Teachers of Layibi College Held on 17th July 1980” was attended and bolstered by Mr. Ocan’s presence.

The meeting hoped to find out which of the parties vying for power at the time was the best to lead the charge to a better Uganda.

The parties in question were UPC, Democratic Party (DP), Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM) and Conservative Party (CP).

It was a crucial time, a time in which sides had to be taken for the betterment of a nation in labor.

The UPC was unanimously chosen as that party by the teachers of Layibi College. Subsequent staff meetings reiterated this stand.

In fact, these meetings culminated in a letter to UPC party president Milton Apollo Obote himself.

It was captured under “Joint Memorandum Written by UPC Teachers in Post-Primary Institutions in Gulu District to Party President, Dr. Apollo Milton Obote, Founder of The Republic of Uganda.”

It was dated 26.8.1980.

In it, in part, it was unreservedly declared that:

“Mr. President Sir, we are sorry to mention to you that some of these people who confused our youths and helped to create “Bayayeism”, also helped in the disruption of our once sound economic and socio-political status. But we are sad to note that some of them are still the same people today trying to maneuver their way to the national parliament through the forthcoming general elections!”

And.

“At this juncture we wish to register our thanks and gratitude to Mwalimu Julius Nyerere; the gallant officers and men of the TPDF; the patriotic forces of the UNLF; and in particular to you Dr. Apollo Milton Obote for the concerted efforts and struggle against the fascist military dictatorship of Idi Amin. Because of the hard struggle and total commitment of the Uganda Peoples’ Congress our beloved motherland was liberated from the iron hands of fascism.”

This was a volatile time, when Uganda had just emerged from the death grip of Idi Amin’s rule. It was also a time the country was going to be tested anew with general elections.

The government and state had all but collapsed. The future was uncertain, with the country on a hair trigger.

Also, the allegiance to political colors was shaded by a society in which people had to sponge off political parties as conduits to a neo-patrimonial system of governance.

Already heavily indebted, the country was broke and broken by a president (Amin) who had ruled by decree.

Mr. Ocan hoped that the pay and perks that were lavished on Ugandan politicians could be used to improve the material circumstances for doctors, teachers, policemen and soldiers.

Then the constituencies the politicians “represented” could be merged into larger electoral constituencies and we could have the 16 districts we had at the time of independence.

The scale and cost of government would be right-sized in order that we cut our coat according to our cloth so that the emperor (Uganda) was redressed in new, resplendent clothes.

A lean and mean government would revert to the 17 ministers and 11 parliamentary secretaries we had at independence.

Then Mr. Ocan and Co. could shut down all these vampiric “authorities” and agencies which were merely hotbeds for patronage.

Candidate Yoweri Museveni said in 1980 that “statehouse is a clearing house for proforma invoices…”, so that colossus (Statehouse) would have to be whittled down to an actual house along with the costs related thereto.

With reduced national expenditure, maybe, Ocan believe, Uganda could have a surplus budget to expand the national fiscus by cutting taxes, improving investment in research and local industries as well as giving subsidies to domestic businesspersons.

This initiative, he believed, would lead to better spread wealth which would also help teachers like Ocan help their families and communities.

It was a dream worth fighting for, Mr. Ocan surmised. That’s why he and his colleagues were so political.

Uganda of 1980 was a country rife with inequalities arising out of tribe, gender, class, social status, geography, and age.

These inequalities were so entrenched that many Ugandans were convinced that civil disobedience and not civility would deliver much-needed equity.

Because, they believed, the rich had swallowed the national cake and left only crumbs along a breadline of unemployment for the poor.

There was a rise in “Bayayeism”, as the teachers pointed out.

The nation had been ghettoized to look ghetto and behave ghetto, that’s why political rallies were akin to war. As candidates brought every weapon to a street fight on behalf of the wretched of the earth.

The seeds of Mr. Ocan’s struggle to improve Uganda situated Uganda’s identity in the revolutionary flowering of national survival, beyond a collective death.

Such death is characterized by a vacuum at its middle, forcing most of its citizenry to the bottom. This while few sit at the top.

As the bottom festered with hordes of youth whose finances had bottomed-out, they felt abandoned by a political class growing fat on government patronage. So Ocan and his colleagues wanted this addressed.

When UPC offered solutions, Mr. Ocan identified with its tragic sense of patriotism: It realized that love for one’s country was a reality looked down upon by the rich and ignored by the powerful.

So Milton Obote and UPC glamorized poverty and gave it a redemptive power by demanding that Ugandans rise above it.

The first Obote government’s ‘Move to the Left’, namely The Common Man’s Charter, in 1969, read thus:

“We cannot afford to build two nations within the territorial boundaries of Uganda: one rich, educated, African in appearance but mentally foreign, and the other, which constitutes the majority of the population, poor and illiterate . . . We are convinced that from the standpoint of our history, not only our education system, inherited from pre-independence days, but also the attitudes to modern commerce and industry and the position of a person in authority, in or outside the government, are creating a gap between the well-to-do on the one hand and the mass of the people on the other . . . Our education system aims at producing citizens whose attitude to the uneducated and to their way of life leads them to think of themselves as the masters and the uneducated as their servants.”

UPC’s vision of progress was a post-modern conception of leadership: subversive of the times yet subservient to a brighter day.

Michael Ocan, the educator, mobilizer, philanthropist and father felt he could address the specific conditions of his country’s existence while escaping the predatory clutches of the unpatriotic.

That way, Uganda would sparkle as that pearl which Winston Churchill marveled at and Michael Ocan so loved.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!