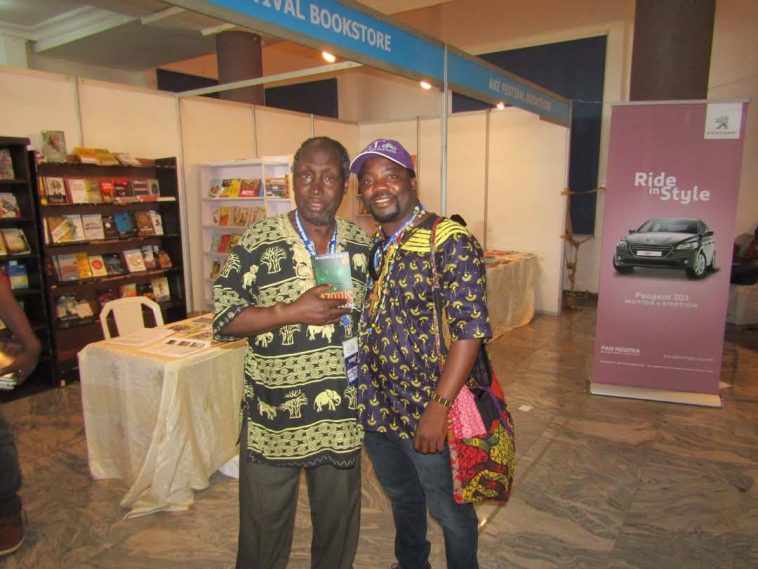

I first met Ngugi in this physical body in 2015 in Abeokuta, Nigeria, when I was invited by Wole Soyinka’s daughter-in-law, Lola, to be one of the speakers at the Ake Arts Festival. My writing life had been deeply influenced by Ngugi, whom I first encountered in the world of literature in 1996 when my mentor, Whyghtone Kamthunzi, gave me his book. I cannot recall exactly which one it was between ”A River Between,” or ”Weep Not, Child.”

In Nigeria, when I met Ngugi, I tried to steal moments of his time, those precious fragments he spared for me to speak with him. I had so many questions, but I could not ask them all. Mzee, many people called him Mzee, so I joined in. Every morning, I made sure to squeeze myself onto his table during breakfast, and whenever I found a small group of people talking with him, I would push myself right in. He even started calling me by name and told me stories about his Malawian friends like David Rubadiri and others he had lived with at Makerere University in the 60s.

On the last day, I forced myself into the bus he boarded, and we traveled together from Abeokuta to Lagos, where he was to catch a flight. We had a police escort the entire way. I remember some motorcycle riders trying to tail our convoy so they too could move fast. Had they known better, they wouldn’t have dared. They were arrested, and we left them with the police as we continued our journey with Ngugi to Lagos to catch his flight. The whole ride was filled with questions, listening to stories, and I realized that Mzee, was full of passion, especially about language, about speaking and writing in our own tongues, about uplifting African languages because language is more than just words, and he had been at the subject for more than half a century, consistently.

One incident about Ngugi’s influence on my writing had occurred in 2003. I wrote a story titled ”A Woman Alone.” It was about a woman banished from her village after being accused of witchcraft, until a missionary, Mr. Bruce, heard her story, took her in, and gave her work as a house help, cleaning his house and cooking, until she began to help her people again, even paying school fees for children.

This story was heavily influenced by Ngugi’s style and themes, to the point where someone commented, “Achimwene, you are really borrowing Ngugi’s style!”

What was fascinating was that when the story was published in Malawi News, a newspaper that usually just printed stories without commentary, they added an editorial note about it, which was a first.

Another time, while I was in America at the Iowa writing program, Peter Nazareth, a renowned writer who had known Ngugi since their youth, was intrigued when I gave a reading at a bookstore where writers and readers had gathered and I mentioned Ngugi. At the time, Peter Nazareth was an Associate Professor in the Department of English, and his duties included advising the International Writing Program. He had grown up in Uganda and had the privilege of knowing Africa’s early writers. Because I spoke about Ngugi, we connected from that day, and he gave me a book he had edited, ”African Writing Today”, published in 1981, and another one, ’Birth of a Dream Weaver.”

My love for Ngugi; for Matigari, Devils on the Cross, Wizard of the Crow, A River Between, Weep Not, Child, and others, was what linked me to Peter Nazareth.

The other book he gave me, ”Birth of a Dream Weaver,” though it wasn’t his own, he felt obliged to autograph it on behalf of Ngugi. He signed it because, in the first chapter, Ngugi speaks of the plays he wrote while at Makerere University and mentions someone who was one of the experts in playwriting, Peter Nazareth himself.

“Peter Nazareth might have understood. Though a year ahead of me in college, he was actually the younger by years; he was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1940, and I in Limuru, Kenya, in 1938. We had worked together for Penpoint, the magazine of the Department of English, but he had just graduated, having passed the editorship on to me….” —Birth of a Dream Weaver, Ngugi—

Ngugi writes again about Nazareth:

“The previous year, 1961, my first ever one-act play, another Northcote Hall entrant, had placed second to the winner, Nazareth’s “Brave New Cosmos,” a Mitchell Hall entrant that subsequently saw light on the Kampala stage. Nazareth, at the time of his Cosmos, had already blossomed into the All-Makerere personality, a presence in music, sports, theater, student politics, and writing.”

As I mourn Ngugi, I mourn someone who was so close to my heart, my life, my writing, yet distant in the flesh. I know that Ngugi has not died, will never die, because he will forever live with us.

And as I remember Ngugi, I also remember all the great things we, as a continent and as a world, failed to do for him. The hope of a Pulitzer Prize, honoring him as one of Kenya’s great treasures, and more. And as we commit his earthly vessel to the ancestors, let us ask that we be granted forgiveness.

That is why people like Lola Shoneyin , and many others, Okey Ndibe , is one of them, our elder brother Mukoma Wa Ngugi , and so many more, deserve respect because they celebrated Ngugi with their entire lives, all their strength, and all their wisdom.

Mzee, continue to walk in the power of our ancestors.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!