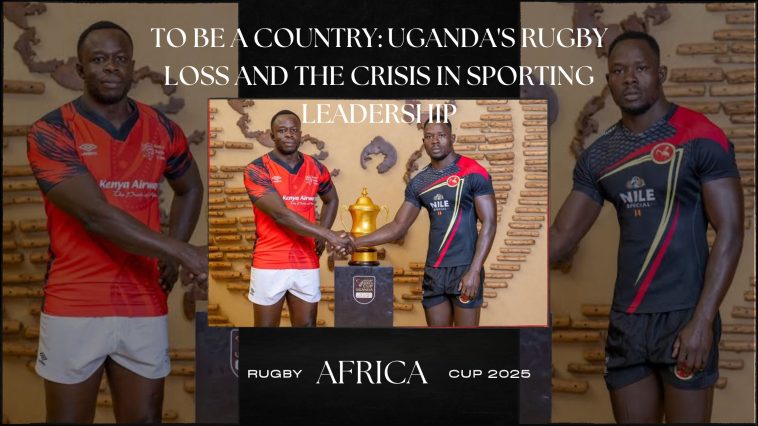

Henry Kissinger once said, “To be a country, you need an army, a currency, and a national soccer team.” In Uganda, whenever we play Kenya especially in rugby the meaning transcends sport. It becomes a statement of identity, dignity, and power in the region. That is why Uganda’s 32-24 loss to Kenya in the Rugby Africa Cup quarterfinals isn’t just a sporting disappointment. It’s a political and cultural embarrassment. In front of 49 million Ugandans, the Rugby Cranes failed to deliver, not because they lacked heart, but because they were failed by leadership.

This loss is not on the players alone. The bigger failure lies with the Uganda Rugby Union Executive Committee (ExCom) and the technical bench, whose strategic blindness and weak systems have made tactical confusion a permanent fixture. We cannot hide from this truth.

Let’s start with the basics: in Rugby Union 15s, the relationship between the scrum-half (9) and fly-half (10) is the heartbeat of any team’s attack. In 60 minutes of play, Aaron Ofoyrwoth passed the ball to fly-half Joseph Aredo only four times. Four. That stat alone tells you there was no spine in the team’s offensive structure. The result? Disjointed phases, broken rhythms, and backs who became mere spectators on the field.

This pattern isn’t an isolated mistake. It’s a product of either a coaching staff with no clear structure or a team where the 9 and 10 don’t trust each other or the game plan. In either case, the responsibility is on the coaching unit. A proper team playing on home soil, with months of preparation, should not present this level of tactical bankruptcy.

We also saw key decision-making flaws on the pitch. Number 8 Pius Ogena, in a pivotal moment at the 50-meter mark, picked the ball from the scrum and forced a blindside move where space simply did not exist. The turnover that followed wasn’t just a misread; it was an indictment of a system that has failed to teach players when to act and when to link up. These aren’t growing pains. These are symptoms of systemic failure.

Another troubling scene: Uganda earns a penalty in front of the posts, with our top pro Philip Wokorach on the field. He misses 8 points off the boot, including that penalty. Worse, he runs down the clock on another opportunity. Was this fear, poor judgment, or an instruction from the bench? Either way, it was a choice made in front of 49 million fans that screamed uncertainty and a defensive mindset. You cannot defeat Kenya with fear.

Then there were the repeated moments when the 9 ran into contact instead of using formed forward pods. The outcome? Isolated carries, turnovers, and frustrated forwards. That’s not rugby; it’s chaos. And it tells us that the team was either poorly drilled or completely unresponsive to coaching corrections. Again, that loops back to the ExCom and the technical bench.

Yes, some players made mistakes, from handling errors to poor breakdown discipline. But we do not publicly shame players representing the flag. We interrogate the systems that set them up to fail. Kenya did not out-muscle Uganda. Kenya out-thought Uganda. They had structure, timing, and synergy. We had potential but no execution.

There is also the question of bench depth and substitution patterns. When Blair Ayebazibwe and Saul Kivumbi came on, the front row collapsed, leading to a crucial Kenyan scrum and eventual try. Substitutions in test rugby are not just about resting legs, they are about maintaining or increasing intensity. Poor substitutions often reflect either misreading the match tempo or simply not having impact players on the bench. Blair Ayebazibwe played about 3 minutes off the bench and he had to be taken off after Uganda conceded twice in that time period. Again, this goes back to selection and coaching foresight.

Beyond the field, what does this result mean to Uganda as a sporting nation? Matches against Kenya are never just matches. They are geopolitical theatre. They are a referendum on institutional effectiveness. When Kenya wins, it is not just their rugby that has triumphed, it is the strength of their sporting governance, their investment in systems, and the maturity of their leadership. Uganda must see these matches as mirrors, not just fixtures. What are we learning from each encounter?

Uganda’s rugby potential is real. Players like Timothy Kisiga, whose 70-meter run sparked hope, and Wokorach, who still carries the magic in his boots, are reminders that talent is not our problem. But when coaching is inconsistent, systems are weak, and strategy is reactive instead of proactive, even the most gifted individuals are rendered ineffective. In modern test rugby, systems win games, not individual brilliance alone.

When a sporting contest between Uganda and Kenya unfolds, it is about more than points. It is a contest of state credibility, of whose system works. It is about our pride as a people who still remember colonial sport as a battleground of superiority. If Uganda cannot assert itself in rugby, how do we command respect in trade, diplomacy, and regional leadership?

This is why the Uganda Rugby Union must be called to account. We cannot keep rotating blame between technical benches and blaming players who are simply trying to carry the hopes of a nation with no support structure. The URU ExCom must answer: what was the plan? Who was enforcing it? And how will they ensure we never see this tactical disarray again?

To move forward, we need reforms that prioritize rugby IQ over political appointments, tactical planning over Instagram squads, and coaches who are held accountable not just by results, but by patterns of play. Training sessions should be aligned to simulate game scenarios. Players must be empowered to read the field and make real-time decisions, not wait for instructions from a bench that may already be behind the tempo.

Moreover, Uganda must rethink its sporting identity. Do we play to win or play to participate? Do we select players based on metrics or legacy? Do we coach with the intention to evolve or merely to survive? These questions must be answered honestly.

Uganda is not short of talent. We are short of structure. And until the URU Executive begins to value the intelligence of the game as much as its pageantry, we will keep clapping for mediocrity.

In the end, sport is not just recreation. It is narrative. And right now, Uganda’s rugby narrative reads like a missed opportunity wrapped in poor preparation.

We can do better. We must do better. But it starts by admitting we are not just losing matcheswe are losing the meaning of what it means to compete with purpose.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!